สารบัญ

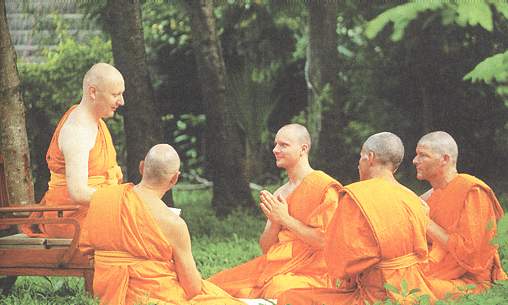

THE FRUITS of TRUE MONKHOOD

'BUDDHISM IN PLAIN ENGLISH' in its series by Phrabhavanaviriyakhun (Phadet Dattajeevo)

CHAPTER 1.

FOREWORD TO THE SAMA~N~NAPHALA SUTTA

The word "saama~n~naphala" means the result or fruit of being a monk — or the "point" of ordaining within the Buddhist religion.

The Buddha taught that anyone who keeps purely and strictly to his vocation as a Buddhist monk would receive many benefits. Most things in the world, which you can do have both "pros" and "cons" but ordaining as a monk has only benefits (if the ordained follow his vocation purely).

The benefits received by a monk come sequentially starting with superficial benefits, which can be immediately seen — such as being honoured by the general public, peacefulness of body, speech and mind, the wisdom to consider matters of the world in a more thorough way, real understanding of life and the world — allowing one to be a good friend to oneself, conducting one's life in uncompromised accordance with the teachings of the Buddha, extracting oneself from the influence of defilements and being a good friend to others — pointing to the right way of life practice for others — and ultimately to attain the paths, fruits and Nirvana itself.

Even if one is unable to attain Nirvana in this lifetime, one's experience, accumulated merit and efforts have not been wasted — but will accrue as the foundation for progress in practice in future lifetimes in accordance with the Buddhist proverb:

In the same way that droplets of water can eventually fill a large pot, the wise accrue even small merits and will one day become filled with such merit.

Once a person is replete with merit, that is the day they can enter upon Nirvana — the ultimate goal of the practice of Buddhism

Brief

Toward the end of his dispensation the Lord Buddha was residing at Ambavana (the Mango Grove) offered by the physician Jiivaka Komaarabhacca close to Raajagaha the capital of the kingdom of Magadha. At that time the reigning monarch was King Ajaatasattu. The King travelled to meet the Buddha for audience with him in order to ask some questions, which had long been on His Majesty's mind — namely the question of the immediate visible point or benefit of ordaining as a monk or becoming an ascetic. The king had asked the same question beforehand of six other contemporary religious leaders but had not received a satisfactory answer.

The Buddha had explained the benefits of ordaining as a monk sequentially starting with the most obvious benefits and continuing with more subtle benefits.

The Buddha explained that the initial fruits of being a monk including elevating one's former status to the status of one worthy for respect.

The benefits at the medium level included the attainment of meditation states at different levels, such as the first absorption, the second absorption, the third absorption, the fourth absorption, all of which make the mind more stable, joyful and peaceful.

The benefits at the high level included the attainment of Eightfold supra-knowledge:

- knowledge that makes you understand your bodily constituents according to reality [vipassanaa~naa.na]

- mental power [manomayiddhi]

- ability to demonstrate miracles [iddhividhi]

- angelic ear [dibbasota]

- ability to read the minds of others [cetopariya~naa.na]

- the recollection of previous existences [pubbenivasanussati~naa.na]

- knowledge of the arising and passing away of living beings [cutuppata~naa.na]

- knowledge that brings one to an end of defilements [aasavakkhaya~naa.na]

Before explaining the benefits of being a monk at the higher and medium level, the Buddha also outlined the monastic discipline:

- - Restraint according to the monastic code of discipline [paa.timokkha]

- - Right livelihood

- - Self-discipline

- - Restraint of the senses

- - Mindfulness and self-awareness

- - Contentment

- - The Practice of Meditation

As a result of the teaching, King Ajaatasattu requested to take refuge in the Triple Gem and to become a Buddhist for the rest of his life. He also asked forgiveness for having caused the death of his own father — King Bimbisaara — and the Buddha granted him forgiveness.

After the return of King Ajaatasattu, the Buddha revealed that if Ajaatasattu had not murdered his own father, he would have attained the fruit of stream-entry as the result of hearing the teaching.

Those qualifying for benefits from monastic practice

Buddhism is a teaching based on cause and effect. The benefits accruing to a monk do not come as the result of the grace bestowed by any god or angel — but as the result of his own earnest efforts and striving in accordance with the Buddhist proverb:

"You shall reap whatever you sow." [DhA. 25/17]

The Buddha laid down clear guidelines for monastic practice. Whoever practices strictly in accordance with those guidelines (not compromising according to his own convenience or whim) i.e. who has set up the proper conditions — then the expected outcomes (the Saama~n~naphala) will arise for him. Thus if a monk wants to see results from his ordination he must practice in accordance with the monastic discipline, not just study it or remember it. He must not be like the monk who can repeat many Buddhist teachings but who never practices in accordance with those teachings and thus has no part in the fruits of ordination just like a cow-herd who does (no more than) count head of cattle for someone else ('s benefit).

Even those who are very familiar with Buddhist teachings but who are reckless with those teachings and do not practice in accordance with them — get no more benefit from the teachings than a herd gets from someone else's cattle despite counting them in the morning as he receives them and making sure he returns the same number in the evening. He never has tasted the curds or the cheese made from the milk.

Why the monastic life is the most noble

The Buddha taught that, the life of the householder is a narrow path which attracts dust. The ordained life is a spacious path. The Buddha referred to the household life as narrow because the opportunities for accruing merit and practising Dhamma are minimal compared to the opportunities of a monk. Householders have to devote a lot of time to their families, earning their living — sometimes so much so that they do not even have time to venerate the Triple Gem each day. Furthermore householders have so little opportunity to study the Dhamma that even though they might refer to themselves as a Buddhist, they do not know how a Buddhist should regard and discern what is good or evil, what are root causes in the world [yonisomanasikaara] in order to avoid blundering into craving and ignorance. Without such discernment, it is the nature of people just to fall under the sway of their defilements such as greed, hatred and delusion. In such a condition householders tend to use up all their time with worldly matters and lose the opportunity to better themselves spiritually. This is why the Buddha called the household life a "narrow path".

It does not make any difference whether you are a distinguished householder in the aristocracy or disadvantaged householders whose life is from hand-to-mouth — the path is no less narrow. In society our acquaintances comprise both good and evil people — sometimes we can choose who we associate with, sometimes not. The less scrupulous acquaintances can be the reason why we add the toll of bad karma for ourselves in various ways. Trying to get the advantage —trying to be competitive, trying to make a profit, which might ultimately lead us to harm others physically — and this is the reason why the Buddha described the household life as "attracting dust".

For as long as we are still leading the household life, it is hard to find time seriously to work on ourselves to extract ourselves from the influence of defilements — and ultimately that extends the length of time we have to spend undergoing the suffering of the cycle of existence — endlessly perhaps if we blunder into committing serious karma of violence or cruelty — and we have to make amends in the hell realms without anyone else being able to help us in our plight. It is for this reason that the Buddha encouraged ordination and praised the nobility of ordination as a "path of spaciousness".

The importance of the Saama~n~naphala Sutta

The Saama~n~naphala Sutta explains to us the reasons for ordination; once one has ordained, how one must practise and not practise; the results of correct practice at various levels of advantage with the ultimate — that the Buddha called the "utmost of the Brahma-faring [brahmacariya]" — until the monk can understand for himself the meaning of the Buddha's words that one's life as a true monk within the Dhammavinaya is the most noble life.

Apart from giving benefit to monks themselves who are already pursuing the Brahma-faring, the Saama~n~naphala Sutta also has many useful messages for the household reader:

1. The Monastic Standards: The information contained in the Saama~n~naphala Sutra is advice at the level of principals and virtues of a true monk — because the Sutta paints a clear picture of the ideal monk — no matter whether they are a Buddhist monk or a monk from another religion — and the sort of principals as virtues he should have.

Such information is useful for householders — to know and be selective about monks — whether they are practising properly or not. Whether they are earnest or lax, whether they can offer us a refuge or not. In such a way, we can avoid paying too much attention to monks teaching unorthodox or possibly damaging practices — and to protect ourselves from becoming a tool for undisciplined monks or from being gullible in the face of monks practising outside the guidelines laid down by the Buddha.

2. Conduct towards Monks: After reading the Saama~n~naphala Sutta, householders will have a clearer understanding of how they should interact with monks in order to facilitate the way they keep the Vinaya — for example, the lesser discipline [cuulasiila], intermediate discipline [majjhimasiila] and greater discipline [mahaasiila] of the monk. If they wish to procure knowledge, goodness or merit from a monk, how should they conduct themselves? Even though they have not ordained themselves, they can still have extended opportunities for accruing wholesomeness — by being a real support to monastic work, by facilitating the emergence of peace in the world.

3. Preparing Oneself for Ordination: Even though householders may not have decided to ordain in the present time, if one day in the future they should decide to ordain, with the understanding he has obtained from the Saama~n~naphala Sutta he still has sufficient understanding to be able to prepare himself correctly to get real benefit from the ordination experience — and will thereby manage to avoid becoming the sort of monk who undermines the future of Buddhism by confusing the public or creating controversy.

When it comes to his time for ordination, he will be able to be selective about where he ordains and with whom he ordains (his preceptor) in order to get real benefits from the ordination experience.

If he should choose to take lifelong ordination, he will truly be able to align himself to attain the paths and fruits of Nirvana. If he should choose, take temporary ordination (such as men who ordain for the duration of the rainy season according to Thai tradition) then his ordination will not be devoid of the advantages highlighted by the Lord Buddha. Ordination will help him to gain Buddhist discretion of wholesomeness [yonisomanasikaara] which will bring direct benefits when he returns to the household life. It will bring indirect benefits to his family, society, and the nation at large — giving life and perpetuity to Buddhism for future generations.

4. Offering the Principals of Buddhism in a Nutshell: the Saama~n~naphala Sutta offers a succinct understanding of both Buddhist principles and methods of practice. From the Sutta the picture is clear that Buddhism is a religion of cause and effect.

Cause in this case means the ways of practice the Buddha gave as guidelines for monastics to follow or avoid.

Effect is the outcome, which the practitioner can expect to receive as a result of practice — there are many successive levels.

The Saama~n~naphala Sutta is thus an incomparable source of information for both monks and religionists who can take its principles as a blueprint for successful administration of religion towards success stability and harmony. For this reason monks need to understand and apply the principles and practices of the Saama~n~naphala Sutra in their own lives, throughout their lives.

Those who master the Saama~n~naphala Sutta will be able to explain Buddhism correctly, succinctly and lucidly to others — even five or ten minutes is enough to give newcomers the knowledge for them to think Buddhism through to an understanding for themselves. Even those subscribing to other religions can learn much from the Saama~n~naphala Sutta in a comparative way to find similarity of principles and practice between their religion and Buddhism — and to reach a state of peaceful co-existence with Buddhists instead of coming into dogmatic conflict.

5. The Acquisition of Perfections: the Saama~n~naphala Sutta is of particular interest to those interested to pursue perfections. The understanding gained from this Sutta will allow those pursuing perfections to do so to the utmost, following confidently in the footsteps of the Lord Buddha and the arahants, without mistake — with the capacity to attain the paths and fruits of Nirvana — and even while still training oneself, to gain guidelines for what it is beneficial to pursue and what to avoid.

From all that has been outlined above, the reader will see that the Saama~n~naphala Sutra is indeed a miraculous teaching — indicating the correct path of practice for monks and those pursuing enlightenment while also giving a precious outlook for practising householders.